- Capitalist economies foster innovation and create growth

- Risk and return are related

- Capital markets are generally efficient

- Diversification is essential

- Asset class returns display randomness and variability of returns

- Financial planning does matter

- Costs matter

- Investment decisions should be based on analysis

- Market timing has significant risks

- The active/passive debate does not tell the whole story

- Investing should be for the long term

- Get in touch

Capitalist economies foster innovation and create growth

Capitalism is what underpins the world’s economy and is overwhelmingly the most successful economic model that mankind has devised. The free market is a simple mechanism that brings together ideas for products and services, as well as the finance required to get them off the ground.

People who invest in an enterprise are taking a risk with their capital and are therefore entitled to share any financial rewards – just as they should accept any losses. This simple principle is followed in every corner of the world, from the dusty markets of third world villages to the boardrooms of the world’s richest corporations.

In more sophisticated markets, the rules of this process are codified by formal capital markets and most investors participate through tightly-regulated exchanges of shares and bonds.

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

Risk and return are related

We believe that it would be very difficult to improve your investment return without taking on board additional risk. In other words, a risk's potential for financial loss is also the reason why you earn a return.

However, it is important to distinguish between good risk and bad risk, as taking on unnecessary risk can leave your portfolio exposed to increased potential for loss. However, higher exposure to the right risk factors leads to high-yield investment, but is not necessarily a guarantee of this. Risk is the premium investors pay for the expectation of a greater return.

Our role as your investment consultant is first to identify which risks offer consistently higher expected returns and which do not, and then to offer you exposure to those risks in a structured, disciplined, cost-effective way.

There is a well-respected relationship within the investment community that goes along the lines that, the higher the target return, the more risk an investor must take. As a result, when constructing an investment portfolio, it is important that the investor determines the amount of risk that they are prepared to take, as this will have a direct consequence on the asset allocation within the portfolio.

In order to determine this, the investor must ask themselves a number of key questions:

- Do you understand the type of risks that you are exposed to?

Investment risk can come in various guises and in order to position your portfolio correctly, it is important that you are aware of and understand them. - What is the time horizon of the investment?

The longer the time horizon, the longer the portfolio will have to recover from a significant drawdown. Thus, investors looking to crystallise their investment in the short term should look to limit exposure to risky assets. - What is your attitude to risk?

Here, it is important to distinguish between risk appetite and capacity for risk. While the investor may be prepared to take a higher level of risk in order to benefit from higher gains, they may not have the capacity for potential loss. Thus, the investors risk profile can be pre-determined by circumstances, such as near retirement, lack of excess capital or the need to remain liquid.

Once the risk profile has been established, the correct asset allocation can be established.

History tells us that different asset classes have different risk and reward profiles. The graph below illustrates the risk and return profiles of the most commonly utilised asset classes.

While past performance cannot guarantee future results, each asset class has a varying degree of risk and potential to over- or underperform over any specified period of time. However, over the long term, the relationship illustrated here tends to hold.

The risk profile and asset allocation are then used to construct the investment portfolio according to modern portfolio theory, utilising the benefits of diversification. Diversification is not only across sectors, but also across geographical regions and asset class. This helps to mitigate potential risks as investments that tend not to rise and fall in tandem will limit exposure to systemic risk and therefore offers an additional tool with which to manage the overall risk of the portfolio.

Types of risk

Inflation risk

Inflation is like a stealth tax, eating away at the value of money. You won't see a smaller cash balance in your account, but you will definitely lose buying power. In other words, the amount that you can purchase with each Pound in your pocket slowly decreases over time.

Many savings accounts fail to pay a return that beats inflation, especially after tax is deducted. So even if you reinvest every penny of your interest, the real value of your savings could fall.

Economic and political risk

Economic and political factors play an important role in the performance of investment markets. Economic factors include economic growth, inflation, employment, interest rates and business sentiment, while political risk includes changes in government, political uncertainty and international conflicts.

Shortfall risk

This refers to the risk of failing to meet your long-term investment target. This could mean that you didn't take on enough risk to get the potentially higher rewards or that you took on too much risk and your portfolio fell in value.

For example, if you are saving for your retirement, putting all your money into a savings account may not build enough capital to produce the income you will need in retirement. On the other hand, you could also be exposed to shortfall risk if you invest in too many high risk assets causing your portfolio to lose value at the wrong time. So investing too aggressively or too conservatively can each lead to shortfall risk.

Country risk

The risk that domestic events – such as political upheaval, financial troubles or natural disasters – will weaken a countrys financial markets.

Credit or default risk

The possibility that a bond issuer will fail to repay interest and capital on time. Funds that invest in bonds are exposed to credit risk.

Currency risk

The risk that changes in currency exchange rates cause the value of an investment to decline.

Interest rate risk

The possibility that the prices of bonds will fall if interest rates rise.

Liquidity risk

The chance that an investment will be difficult to buy or sell.

Manager risk

The chance that a pooled fund will under-perform due to poor investment decisions.

Market risk

The risk that any market such as equities, bonds, property or cash, may decline.

Sector risk

The risk that a particular sector within a market, such as the oil and gas sector, or the travel sector, may decline in value. For example, if oil prices surge, the oil and gas sector might rise whereas the travel sector might fall due to rising fuel costs.

Specific risk

The risk that a specific share, bond or fund you've invested in performs badly.

Volatility risk

As we saw earlier, different types of investments fluctuate in value over time. This is referred to as volatility and is often used to assess the potential risk associated with an investment.

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

Capital markets are generally efficient

Capital markets are the best mechanism we have to calculate the value of an asset. The value of that asset should reflect its potential future return. Many investors believe that they are able to price assets more accurately than the market.

Investors perform research and analysis to arrive at a price for an asset. If the market price is below their calculated price, they might buy that asset to make a profit when it rises. But, however carefully they make their calculation, they never base their prediction on more than an estimate. Some estimates will be right and some will be wrong.

Research shows that very few people are able to make consistently accurate estimates over a reasonable period of time. For this reason, we do not use predictions about markets or prices in our portfolios.

We apply this principle across our investment philosophy, which means that we do not buy individual stocks that we think will outperform the market; nor do we weight investments towards countries or regions that we expect to do well. Instead, we use investment funds with broad exposure to the whole market and allocate assets to countries in proportion to their relative size in the global market.

We therefore accept that the market, powered by the wealth-generating capability of capitalism, provides an adequate rate of return. We do not try to beat the market with predictions; instead, we harness the returns of the market through discipline and structure.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

The astute investor will constantly search for alpha within the market; the opportunity to realise gains from market inefficiencies has been a dominant strategy for many years. To this day, many investors will scour financial newswires and data feeds, analyse company financial statements and monitor potential deals and mergers. The aim is to identify the opportunities for arbitrage or find stocks which are over or undervalued on the stock market relative to their actual value. This strategy revolves around the idea that markets are generally inefficient and thus there will always be value to be found given the correct knowledge and market timing.

However, around the mid-twentieth century, this idea came under scrutiny as a number of academics began to question the nature and efficiencies of financial markets. Although there had been prior research surrounding the topic, Eugene Fama published a landmark paper in 1965 in which his empirical analysis concluded that stock market prices follow a random walk[1]. He went onto explain that, given his conclusions regarding stock market movements, there were questions to be asked of both technical and fundamental analysts. He continued his research in 1970 with further empirical studies[2] and concluded that an efficient market is one in which prices fully reflect all available information. The concept of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) has since steadily gained momentum.

More recently, following the stock market crash of 1987, the internet bubble of the 1990s and more recently the events surrounding 2007/08, many questions have been raised regarding the validity of the theory. Recent events have suggested that there are, in fact, inefficiencies within the market and thus fundamental analysis remains a core component for investor gains. However, in his book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street[3], Burton Malkiel illustrated that although the market may exhibit periods of inefficiencies, one cannot consistently outperform market averages.

In other words, while active fund managers will periodically outperform the market average, the probabilities of such an eventuality diminish over time and consistently above market returns become unlikely. As a result, the longer the time horizon the more prevalent the EMH becomes and thus, given our approach that investing is for the long term, our belief remains firmly within the efficient market.

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

Diversification is essential

Diversification is the principle of spreading your investment risk across various asset classes, regions and sectors. We ensure that our investment portfolios hold the shares and bonds of many companies and governments in many countries around the world.

We choose to invest our clients’ assets in many thousands of individual investments because we believe in the power of capital markets rather than individual predictions or judgments. This means that the negative and positive influence of each individual investment is reduced, producing, on aggregate, less risk in our portfolios.

Diversification across an investment portfolio remains one of the cornerstones of a sound investment strategy. The idiom “do not hold your eggs in one basket” is particularly pertinent in this instance.

However, there is far more to be achieved through diversification than simply mitigating systemic risk. It has been researched and documented on many occasions that a correctly diversified portfolio has the ability to enhance market returns.

Markowitz and “Portfolio Selection”

Although the concept of diversifying risk has been recognised for centuries, it was back in the 1950s that the idea was formalised within the financial arena by Harry Markowitz in his 1952 paper “Portfolio Selection”.

Markowitz used mathematical formalisation to postulate that the investor should look to maximise the expected portfolio return, while minimising the variance of return[1]. This concept may seem elementary within the modern investment community; however, Markowitz's paper remains a core basis for many investment philosophies today.

Since the 1950s, there have been a number of developments to the theory, of particular relevance is the idea portfolios will yield higher returns through diversification[2]. According to a paper by Booth and Fama, given constant asset allocation weightings, diversification has the ability to add to the portfolio’s compound return.

When it comes to diversification, it is important that all facets of the portfolio are covered. More specifically, diversification should look deeper than simply asset allocation. The investment should also be spread across market sectors, credit ratings, maturity structures and, importantly, geographic regions.

International diversification, or a move away from domestic markets, should be a core consideration and failing to do so is often referred to as a “home” or “domestic” market bias.

Thus, while diversification will be a familiar concept to most, if undertaken correctly, a well-diversified portfolio will not only mitigate risk but also enhance portfolio returns, and as Markowitz postulated, maximise returns while minimising risk.

Asset class returns display randomness and variability of returns

The investment community is constantly producing research and analysis pointing toward a particular area or asset class within the market which is positioned to outperform. However, history tells a different story.

The following table (supplied by BlackRock) demonstrates a ten-year snapshot of asset class returns between January 2004 and December 2013.

The patchwork dispersion of colours shows no predictable pattern and helps illustrate why we believe it is pointless to try to predict which asset class, region or sector will be at the top next year or the year after. As a result, we do not attempt to guess which asset class will outperform, but rather build investment portfolios which capture growth through exposure to areas which have historically offered the highest returns.

Financial planning does matter

Investing money in a tax-efficient manner is an essential boost to your overall investment performance. This entails the correct use of tax wrappers, tax reliefs and the avoidance of tax "errors".

The financial planning process ensures that the trade-off between flexibility and tax efficiency is managed within your personal framework of financial goals and limits. The process also ensures that the risk/return trade-off is appropriate for you and is managed on an ongoing basis, as your personal situation changes over time.

This element of the investment process is often overlooked and can have a detrimental effect on your overall portfolio performance. Determining current and future cash flows are crucial if you are to maximise your investment return, reinforcing the crucial importance of a well drafted financial plan.

Costs matter

If competition drives prices to fair value, one might wonder why under performance is so common. A major factor is mutual fund costs. Costs reduce an investor’s net return and represent a hurdle for a fund.

Before a fund can outperform, it must first add enough value to cover its costs. All mutual funds incur costs. Some costs, such as expense ratios, are easily observed while others are more difficult to measure.

The question is not whether investors must bear some costs, but whether the costs are reasonable and indicative of the value added by a fund manager’s decisions. The data shows that many mutual funds are expensive to own and do not offer higher value for the higher costs they incur.

Let’s consider how one type of explicit cost - expense ratios - can impact fund performance. In the chart below, equity funds in existence at the beginning of the one, five and ten-year periods are ranked into quartiles based on their average expense ratio.

Fund expense ratios range broadly. For the one-year period (2012), the median expense ratio was 1.1% for equities. In 2012, funds in the lowest quartile cost equity investors an average of 0.48%. The most expensive quartile, at 1.66%, had an average cost that was three times higher.

Are investors receiving a better experience from higher-cost funds? The data suggests otherwise. This is especially true over longer horizons, when the cost hurdle becomes too high for most funds to overcome. Over the five-year period, 31% of the low-cost equity funds outperformed versus 17% of the high-cost funds. Over a 10-year period, 21% of the low-cost funds outperformed versus only 10% of the high-cost funds.

The cost of an investment is a factor that many fail to adequately account for when constructing an investment strategy and portfolio. When considering the performance of an investment, one should always consider the costs involved.

According to research conducted by the Financial Services Authority (now the Financial Conduct Authority) back in 2000, one "must invest about £1.50 in an actively managed unit trust or through a life office in order to obtain the market rate of return on £1; and that obtaining the market rate of return on £1 requires an investment of about £1.10 to £1.25 in an index tracker.” [1]

Its hard work to run an actively managed fund that consistently beats the market. In an effort to achieve this, there are a number of strategies which can be employed: top-down, bottom-up, event-driven, value and growth investing, technical or fundamental analysis and the list goes on.

While many of these strategies may differ, a common element through all of them is that the active manager needs to draw upon a team of highly skilled individuals in order to conduct and implement these strategies. This will of course come at a cost and as a result the fund must charge a higher premium, essentially raising the level of performance required to offer the investor a return above the benchmark [2]

Coupled with this, there have been a number of recent academic articles suggesting that there are very few active managers who, on average, have the ability beat core market benchmarks, specifically when costs are taken into account [3]

We take the negative impact that costs can have on your investment portfolio very seriously. As a result, we have specifically constructed our portfolios with this issue in mind. In line with this, our strong focus toward the passive, and smart beta environment helps to minimise costs without the risk of under performance.

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

Investment decisions should be based on analysis

Markets are frenetic, energetic, ever-changing entities that require people who are actively involved in them to be constantly plugged in and switched on. However, this does not mean that as an investor, you must be too.

This is a mistake many investors make - believing that to be successful they must have their finger on the pulse all the time. The investment management industry and financial press perpetuates this myth with daily chatter that offers rolling tips, predictions, warnings, speculation and advice. This material is produced by competitive media and funds sales industries that survive by attracting attention to themselves.

But virtually none of this information is of use to investors; in fact, it is distracting noise that can bully people into taking ill-advised actions. It is entertainment, not information.

Our investment philosophy is based on information and knowledge, not noise or entertainment. It is rooted in the work of cool-headed academics with no vested interest in selling investments or filling column inches.

This diagram shows that there are four categories of investment style. Some investors try to time markets to their advantage and/or select securities which they believe are mispriced. Investors who do not believe it is possible to make predictions about stocks or market performance - who cannot predict the future - are in box four.

We are in box four:

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

Market timing has significant risks

Markets have up and down days. It’s virtually impossible to predict their direction on a day-to-day basis.

Trying to predict their movements results in an attempt to time various sectors of the market.

Asset classes investors are required to move in and out of the market in order to enhance returns. Being out of the market can be costly.

The graph below illustrates how a hypothetical equity investment would have been affected by missing the best performing days over a 20-year period from 1994 to 2013. The benchmark investor who remained invested over the entire period would have accumulated £41,946, while the investor who missed just five top performing days would have only accumulated £28,858.

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

The active versus passive debate does not tell the whole story

Investment styles are often categorised as active or passive.

An active investor is one who makes decisions about holding one investment over another. Most active investing is done with the use of active, stock-picking fund managers, in other words through mutual funds or an open-ended investment company (OEIC). Passive investors, on the other hand, are willing to accept the market rate of return and usually pay smaller fees than active investors. Most passive investing is done with the use of passive tracker funds and/or ETFs.

Research demonstrates that the average fund manager does not generate enough excess return over and above the market return to justify their fees. This is used as the primary argument against active fund management and in support of trackers.

Research also indicates that a certain percentage of active fund managers do outperform. However, as that list of outperforming managers is a moving target, it is clearly a difficult - if not impossible - task to consistently identify when to buy and when to sell those managers.

On the other hand, tracker funds and ETFs that track indices, display significant tracking errors in the indices they seek to track. Those tracking errors can be well in excess of the fees that active managers charge. In addition, the indexes that passive managers track vary significantly, are decidedly random in their construction and create trading strategy problems for passive funds. ETFs display complexity and counter-party risks that make them very hard for the average investor to fully understand.

Our investment philosophy is to be neither passive nor active, but to use the best of both and mitigate against the risks of each. Our investment process targets market-beating performance through structured exposure to dimensions of higher expected return and uses methods of portfolio construction and implementation that enhance performance relative to the average investor.

We believe that over time:

- The average active investor will do worse than the market because they are paying the highest fees

- Our investment approach will outperform both due to reasonable fees, exposure to dimensions of higher expected return and intelligent portfolio implementation

We provide expert investment advice and services tailored to your personal circumstances

Investing should be for the long term

Financial markets can be volatile, with downturns as much a part of investing as bull markets.

However, short-term drawdowns in markets should not dissuade investors from the long-term returns on offer from markets. In fact, short-term drawdowns highlight the need for a long-term approach to investing.

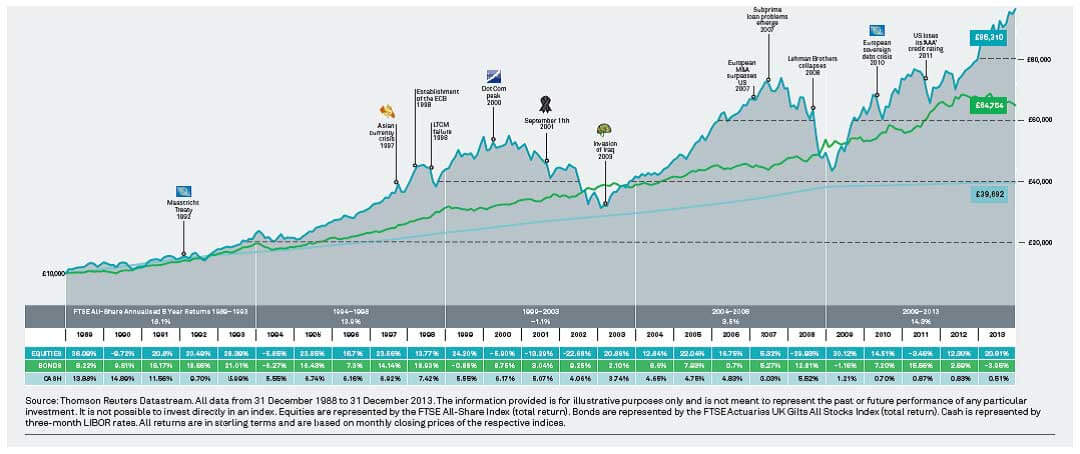

The chart below shows that despite market volatility, an investment in the FTSE All-Share 25 years ago would have grown to more than nine times its original value by December 2013.

Resources

- Fama, E. (1965) The Behaviour of Stock Prices

- Fama, E. (1965) Efficient Capital Markets A Review of Theory and Empirical Work

- See “A Random Walk Down Wall Street: Including a Life-Cycle Guide to Personal Investing

- Rubenstein, M, “Markowitz’s “Portfolio Selection”: A Fifty-Year Retrospective”, The Journal of Finance (2002)

- David G. Booth & Eugene F. Fama, “Diversification Returns & Asset Contributions”, Financial Analysts Journal, May/June 1992

- James, K “The Price of Retail Investing in the UK” 2000

- French, K (2008) Cost of Active Investing

- Carhart, M (1997) On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance; Jones, R & Wermers, R (2011) Active Management in Mostly Efficient Markets; Malkiel, B (2005)